Understanding the Horse's Sole 8-16-05 Pete Ramey

The sole of the

foot is the most abused and misunderstood part of the domestic

horse (with the possible exception of its digestive system).

I’ve been guilty of it, too. As a horseshoer it always seemed

necessary for me to routinely cut the sole at the toe, and in my

early days as a barefoot trimmer I thought it was desirable to

thin it at the back of the foot. When I began both professions,

I was taught to view the sole as an idle passenger; trimming the

hoof wall to certain parameters and then trimming or relieving

the sole to match. Now I see the sole as the ultimate guide for

hoof trimming; keeping the heels, bars and quarter walls

1/16-1/4 inch above the natural callused sole plane. (See

http://www.hoofrehab.com/HeelHeight.html for exceptions.) When I think back on the

past and compare it to my results now, I shudder at the

comparison. My own learning curve has been a long one. I hope to

shorten it for you, here.

It is a confusing

subject, though. It can be difficult to distinguish between

healthy sole that should be preserved, false sole that should be

removed, false sole that needs to stay around as long as

possible because the new sole underneath is immature, shedding

sole that needs to be removed because fungal infection

underneath is eating away at the new sole that is trying to

grow, unsupported sole under flared walls that needs to have

pressure relief………….. The list goes on, and it seems the more

you learn, the less you may understand what needs to be done.

Since the sole is the first line of defense between the horse

and the ground, its proper management is crucial to soundness.

Luckily we have a very reliable guide. The seams between the

sole and frog – the collateral grooves – are the most reliable

and important guide we have for determining the needs of the

foot. A full understanding of their significance and the

information they offer will give you “x-ray vision” when you

look at almost every hoof.

Let’s start with the

foundation. When viewed from the side, a naturally shaped hoof

should have an arch from front to back much like the arch of

your own foot. The coffin bone shapes the front half of the foot

and in a standing horse, should thus mirror the front half of

the arch, or be elevated slightly in the back. The lateral

cartilages form the foundation for the back half of the foot,

but with more flexibility.

During normal

locomotion, the horse should load the initial impact force on

the more flexible back of the foot giving the horse an

incredible ability to dissipate energy. Much like the rubber

tires on your car, this flexibility immediately reduces the

amount of shock that must be dissipated by the rest of the

system.

As the foot reaches

maximum load, the arch is pressed flat, giving a ground parallel

orientation to the coffin bone and to the lateral cartilages.

Then, the horse lifts the heels as the stride is completed,

leaving the rigid front half of the foot the tremendous job of

driving the horse forward.

The underside of the

coffin bone and the lateral cartilages are vaulted like a dome.

Looking at this dome from the bottom gives you the impression

you are looking into a bowl and the corium that grows the sole

of the horse is attached to and grows from this foundation.

According to measurements taken from wild hooves and healthy

domestic hooves the sole should be 5/8- to 3/4-inch thick and

uniformly cover the vaulted underside of the lateral cartilages

and the coffin bone. This is not something we have to do for the

horse. It will take this shape naturally if the horse gets

plenty of movement on its bare hooves. We must allow this sole

to callus into very dense material if it is to be expected to do

its job of protecting the underside of the horse. Its surface

area is huge when compared to that of the hoof wall’s ground

surface, so it is actually the sole that is bearing the lion

share of the horse's weight (on any yielding surface, this is

true, whether the hoof wall is 1/8-inch shorter than or 3/8-inch

longer than the sole).

The sole was

designed for this, though, and generally does this job very well

as long as humans don’t come along and routinely thin it.

Personally, I can run very comfortably on gravel while barefoot,

but I know I could not even walk on grass if someone were

constantly cutting the soles from my feet; even if they only did

it in one tiny spot and left the rest of my callous intact. A

broken bottle retaught me this lesson on a recent family camping

trip. I had plenty of calloused areas left on my feet, but the

dime-sized area I lost made my own boots seem like “too little,

too late.” I was basically lame for a week, and a month later,

I’m still not “gravel crunching” without my "hoof boots."

Soles of horses and

humans can be regrown very quickly, but callused sole is another

story. Callused sole is simply a huge amount of sole material

packed into a thinner space. It takes time to build adequate

callus. So should we just leave horse soles alone and let them

callus and build at will? Usually yes, it’s just that simple-

leave the darn sole alone. There are exceptions and

this muddies the water, though. When a shoe has been on a horse

or if it has been stall bound, the sole can build into thick

layers. Domestic donkeys and minis tend to grow too much sole no

matter how much they move on our soft pastures. Sub-solar

abscessing can leave large false soles in its wake. In arid

environments, the sole may never exfoliate on its own. Sometimes

we do need to trim away this excess to allow hoof function and

normal callusing of the real sole.

How do we tell the

difference? How do we know when we have adequate thickness,

excess thickness, or not enough? Easy. Nature gave us a

trustworthy guide in the collateral grooves. If we learn to read

them, we will never have to wonder what needs to be done or not

done to the bottom of the foot. The very special thing about the

collateral grooves is that they are very consistent in their

depth to the underlying inner structures. If you take cross

sections of a cadaver hoof, you’ll find that it is about

7/16-inch (9mm) from the bottom of each groove to the sensitive

corium -- whether the rest of the sole is too thick or too thin.

This means that if a horse has too much sole at the outer

periphery, the collateral grooves will be too deep. If there is

not enough sole thickness at the outer periphery, the collateral grooves will be too

shallow. To my knowledge, only a sub-solar

abscess can push the grooves farther from the coffin bone, and

deep, thrush-like infections are the only condition that causes

them to become closer to the corium.

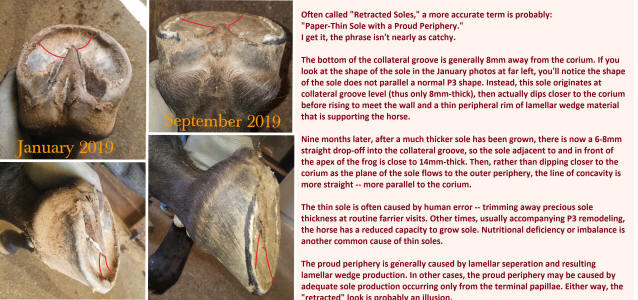

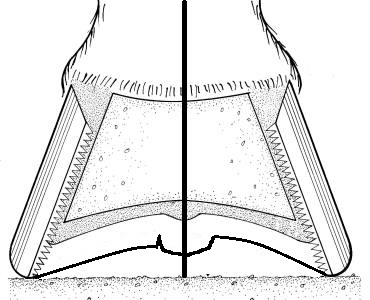

Above, are two

flat feet with very different needs – at first glance, the

only difference between the two might be the collateral groove

depths. The hoof on the left needs an aggressive trim, and the

hoof on the right needs the entire bottom of the foot left

completely alone. All we have to do is understand how deep the

grooves are naturally, and we will immediately be able to tell

if the inner structures are too close to the outdoors or too far

away. This applies to the front of the foot and to the back. I

can’t put exact dimensions to this, because different coffin

bones have different amounts of solar concavity, and of course

it varies by hoof size (though not much). A little bit too much

sole bothers horses far less than having too little, so I tend

to begin by erring on the side of caution. Wild hooves and

healthy domestic hooves with uniform sole thickness tend to have

their collateral grooves (at the deepest part) about ¾” off the

ground at the apex of the frog, and about an inch off the ground

toward deepest point beside the bars. These measurements can be

taken by laying a rasp across the foot and measuring down to the

bottom of the groove.

If this measurement

is ¼” deep at the apex of the frog, you can very safely assume

that there is not enough sole between the coffin bone, its

sensitive corium, and the outdoors. It must be allowed to build.

If this measurement is 1 ½” deep, you can very safely assume

material could be removed. The same exact logic applies to the

back of the foot as well – the back of the foot needs 1/4”-1/2”

more depth than at the apex of the frog to provide a 3-5 degree

positive palmar angle.

These

measurements are far more critical to the horse than toe length

or heel height measurements based on the highly mobile

coronet/hairline (read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Coronet.html ). The coffin bone and lateral cartilages often

descend into a lower position in the hoof capsule and this

yields a hoof capsule that is longer than natural. This is

unhealthy, of course, but trimmers and farriers who ignore this

fact and trim to heel or toe length dimensions add insult to

injury by overexposing the nerves in the corium on the bottom of

the foot. Thinning the sole tends to cause the inner structures

to move lower and lower, lengthening the overall hoof capsule.

The flip side of this, is that allowing the sole to build and

callus at optimum thickness drives the inner structures upward

(read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/DistalDescent.htm ).

The coronet moves down the skeleton, shortening the hoof capsule

to natural proportions as the callus builds. The center and

right pictures below show the natural sole thickness and

concavity of a wild horse's foot. Read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Seasons.html

for the exceptions to the need for a

deeply concaved sole.

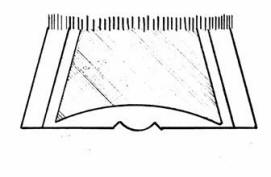

In the drawing above

left; you can see our goal when we are faced with a shallow

collateral groove. The left side of the pictures show how we

turn the flat foot with shallow collateral grooves into a

concaved foot by building adequate sole thickness. The right

side of the picture shows the common mistake of trying to carve

out solar concavity; thinning an area that is already too thin.

We will build solar concavity as we build sole thickness.

Contrary to the way the picture must be drawn, the hoof

generally does not lengthen during this process. The coffin bone

and lateral cartilages are pushed upward (relative to the

hairline) as the sole builds, keeping the hoof capsule the same

length or often dramatically shortening it. Burn this drawing

into your brain and give it a lot of thought – if you are a hoof

care provider, it may be the most important thing you ever see.

If the sole-building

process is only partially complete, you will see a flat spot

adjacent to the white line and a concaved shape to the area of

callused sole closer to the frog. This flat area reliably shows

you where the sole is still too thin. It is very important to

note that as the horse tries to build this natural sole

thickness, it will often prioritize key areas where the sole

thickness is needed the most. The result will be "lumps or

bumps" on the flat area or along the sides of the frog. Many

trimmers routinely trim away these bumps; working against the

horse's attempts to build adequate solar concavity. You must

visualize the natural flow of the individual horse's solar

concavity and determine if that flow goes all the way out to the

white line, without going flat, anywhere.

That lump may be the only correct spot on the whole foot. If it

falls within the "imaginary bowl" of natural concavity, you

should leave it and hope it spreads over the rest of the sole.

To visualize proper sole thickness using the collateral grooves, use the wild hooves or a healthy domestic hoof with adequate sole thickness. Think of the collateral groove as the bottom of a bowl, and natural solar concavity flows up and out from there. Anything sticking above this bowl should probably be removed. Any area below this bowl should be left alone and allowed to grow. Misunderstanding this is where people tend to hurt horses. Again, when the bowl isn’t deep enough, there is not enough sole at the outer periphery. There will be a flat spot in the sole in the outer perimeter touching the white line. You’ll generally see the flow of the natural concavity making its way out from the frog, but then it will flatten out where it is too thin. Study the previous line drawings if this is still not crystal clear.

Note:

When P3 has become remodeled, losing mass at its outer

periphery, the sole can be of uniform and adequate thickness and

still be flat at the outer periphery because it mirrors this

shape of the bone. The collateral groove depth at the apex of

the frog will be shallow in these horses as well, even with

adequate sole thickness. If a horse

seems to have difficulty growing sole, examine the sole

thickness and the shape/mass of P3 on a lateral radiograph.

These horses will usually have a

permanent reduced capacity to grow sole. Optimize the diet (http://www.hoofrehab.com/Diet.html), use

exercise in boots with padded insoles (http://www.hoofrehab.com/bootarticle.htm

and

http://www.hoofrehab.com/GloveMod.html),

grow out all wall flares (http://www.hoofrehab.com/WhiteLineDisease.html), and let the horse spend

loafing time in deep beds of pea gravel to stimulate sole

growth. Use

www.hoofarmor.com

applications or

www.Equicast.com

to eliminate external wear during the

sole-building process.

In the beginning, we don't know exactly how much concavity is needed by the individual horse, so to be on the safe side, assume it should be 3/4" (18mm) at the front and 1" (25mm) deep at the deepest point beside the bars. These measurements are toward the maximum you will commonly find, and always a good place to start. After we build some depth, the shape of the horse's natural solar concavity will start to emerge and we shift to trusting that shape.

Note: When heels are contracted, the lateral cartilages will be bent up into a higher arch. This yields collateral groove depths that will exceed 1” with the same target 1/2”-3/4” sole thickness. In these cases, trusting the callused sole plane is more accurate that dictating a specific collateral groove depth. Also, for additional important heel height variables, read http://www.hoofrehab.com/HeelHeight.html.

The hoof above

almost has complete sole thickness, but you can see a slight

flattened area in the sole at the toe, indicating that a little

more depth could be built there. Too many trimmers tend to cut

concavity into this flat region, thinning an area that is

already too thin. The result, again, is a flatter foot as the

undermined coffin bone is free to migrate downward under the

horse's weight. Concavity must be built up, and cannot be cut

in.

In Jaime Jackson's

wild hoof specimens (above), the collateral groove at the apex

is only 1/2" deep within the solar concavity. If this were a

domestic horse in our care we would know that natural sole

thickness has been achieved because there is no flat spot

adjacent to the white line at any part of the sole. This natural

shape of the callused sole over-rides our original ¾-inch

"starting guess," whether it turns out to be deeper or

shallower. If only these principles were more widely

understood......

I personally see

more horses lamed by the farrier’s rasp than by every other

means combined. I would love to see a rasp designed to deliver a

strong electric shock to its handler if it gets closer than

5/8-inch away from the bottom of any collateral groove for any

reason. A hoof knife that shocks its handler

if it gets closer than 3/4-inch away from a coffin bone or

lateral cartilage would be nice as well. I would spend my very

last dime, buying them and distributing them all over the world.

There is no excuse for such a blatant misunderstanding of the

foot. Most subsolar abscesses and EVERY coffin bone sole

penetration I have ever seen came along in the wake of previous

trimming away of the sole material under the coffin bone or

lateral cartilages. This is a strong statement, I know, but

painfully true.

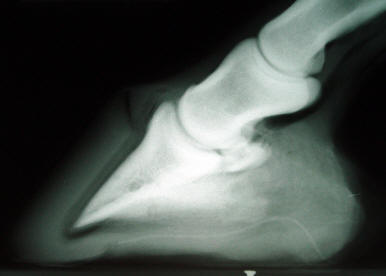

The corium

surrounding the tip of P3 in the above radiograph was exposed to

the outdoors. The attending veterinarian diagnosed chronic

laminitis, sole penetration and calcification of the lateral

cartilages. The deep rasp marks and the huge flattened area were

still visible in the sole in front of the frog! This work was

done in preparation for a "corrective" shoe. The collateral

groove depth at the apex was zero, and the groove depth at the

back of the foot was 1-3/4". The conditions here should be

immediately obvious to the educated naked eye, but I've seen

this too many hundreds of times to count. Why do so few notice?

The above right radiograph was taken six months later. I simply

allowed the horse to build adequate sole thickness under P3,

grew in a [more] attached toe wall, and kept the heels 1/16"

above the sole plane. This restored 100% soundness and usability

to the horse.

I try very hard not

to point fingers at the previous farrier on cases like this. It

would just come across as "putting down the competition" and I

would probably spend my life as a witness in courtrooms or get

beaten to death by an angry farrier, so I skillfully sidestep

questions from veterinarians and owners about the real causes of

these problems to keep peace. It makes my life easier, but I'll

probably eventually go to hell for that dishonesty.

While barefoot

trimmers are usually not guilty of sole abuse at the toe, many

of them are very guilty of having the same misunderstanding at

the back of the foot. Like the coffin bone at the toe, the

sensitive structures at the back of the foot can prolapse, or

move downward relative to the coronet. Many trimmers try to get

the heels and bars trimmed into “wild horse parameters” based on

measurements from the hairline too quickly and thin the sole at

the back of the foot. The results are sensitivity, sole bruising

and then abscessing. The sole is designed to bear the horse, but

only if it is well callused and naturally thick.

In the photos above,

the left pictures are of the setup trim, and the right pictures

are post-trim, four months later. The sole has built so much

depth and concavity because it was completely left alone during

this process. I was treating the horse for very thin soles and

separated laminae. Notice that at the setup trim, the collateral

groove at the apex of the frog is only about 1/8" deep and the

sole in front of the frog goes flat. It should be obvious by

this that the sole under P3 is very thin. Four months later, the

sole has thickened, placing the collateral groove 1/2-inch deep

at the apex of the frog and solar concavity has built in to

mirror the shape of the bone. All of the white line separation

has grown out, with the exception of a small bit remaining at

the toe. Read

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Coronet.html.

Now look at the

heels and bars. Early in my career, I was taught to view these

bars as being "laid over" or bent, and to trim the bar and sole

together to straighten them. Now, however, I see the flat area

in the sole at the back of the foot as an indication that the

sole is too thin in that spot. The bar is not laid over, but is

chopped off too short because of this missing solar depth. Over

the next four months, I simply let this sole build, keeping the

bar and heel wall lowered to the height of the sole. When the

sole built to adequate depth, the bars follow the resulting

natural concavity and straighten themselves. Read

When I used to trim

this concavity, rather than building it, my horses were less

sound and their soles were much flatter. In four weeks’ time,

the flat spot would return, and I would trim it again. Was I

seeing success with hoof rehabilitation and with barefoot

performance horses? Yes I was, but I had no idea at the time how

much better things could be. Now, in hindsight, it's easy to see

why.

Another common

failure of barefoot trimmers is inadequate boot use. It is

important to understand that horses with less than 5/8-inch of

well-callused sole at any spot on the foot simply don’t have

enough armor for safely carrying the weight of a rider over hard

or rocky terrain. Use boots with padded insoles until adequate

sole has been grown.

Whether it is a

shoer thinning the sole at the toe or a barefoot trimmer

thinning the sole at the back of the foot, the result is sole

sensitivity and bruising of the solar corium. This bruising

often causes sub-solar abscesses and leads to P3 remodeling and

permanent corium damage (a reduced capacity to grow sole). Hoof

managers must realize this because sole sensitivity and

sub-solar abscesses in horses with adequate sole thickness and

callus are about as common as white horses that won’t roll in

the mud. Using the collateral grooves as the

guide will keep you out of this trouble.

The same working

knowledge of the collateral grooves will also tell you when it’s

time to get very aggressive with the sole. The collateral groove

in the donkey hoof above is 1- 1/2" deep. We can very safely

create the "natural bowl" of solar concavity, dramatically

reducing this excess. In this case, I am keeping my nippers

¾-inch away from the bottom of the collateral grooves at all

times. After this one-time, large reduction, you should watch

for the natural shape of the individual's callusing to emerge

and trust that shape, rather than the "experienced guess" you

started with. The collateral groves at the back of this foot

show you that the sensitive structures have migrated downward,

and trimming these heels into "wild horse parameters" would

actually cause you to make the grooves too shallow and even cut

the lateral cartilages, in this particular case. The sole at the

back of this foot must be preserved to drive them upward.

The pictures above

demonstrate the information the collateral grooves have to

offer. The first picture is before the setup trim. The horse was

diagnosed with navicular disease and with a coffin bone rotation

over 20 degrees. The second picture is the same hoof eight

months later, and before a six week maintenance trim; sound and

working for a living. The sole was not trimmed at any time

during this process.

The collateral

grooves at the setup trim are 1/16 inch deep at the apex of the

frog and 1" deep at the back of the foot. The wide distance from

the from the collateral groove at the back of the foot to the

hairline shows that the lateral cartilages have migrated

downward and these heels cannot be significantly lowered without

thinning the sole and robbing the horse of necessary protection.

At the apex of the

frog, the shallow groove and the flat area of sole in front show

us that the coffin bone is very close to the outdoors. In fact

you can clearly see its imprint on the sole, with a significant

lamellar wedge between the sole and the wall. Using this

information and judging the severely long hoof capsule, we know

the coffin bone and lateral cartilages have migrated downward in

the hoof capsule (or more accurately, the coronet has migrated

up the limb). If we cut the hoof into "natural parameters"

measuring heel and toe length from the hairline, we would trim

the coffin bone itself – rasping the coffin bone is bad.

Instead, I just

trimmed the heels, quarter walls and bars to 1/16" longer than

the healthy sole and relieved the pressure on the disconnected

toe walls. Eight months later, the apex of the frog is buried

nicely into 5/8" of solar concavity. The collateral groove at

the back of the foot is 7/8" deep (after trimming the walls to

1/16" longer than the sole). There is adequate callused sole

everywhere.

Additionally,

this callused sole has driven the inner structures much higher

in the hoof capsule; dramatically shortening the hoof. The toe

wall is much shorter, and the collateral groove at the back of

the foot is now above the hairline. In other words, the coronet

and the rest of the hoof capsule has migrated over an inch down

the skeleton, into a more natural position relative to P3 and

the lateral cartilages. The result is a naturally short heel and

toe, with adequate solar concavity and thickness along the way.

It was comfort, proper movement and the growth of a well

attached hoof wall that shortened this hoof capsule, not the

knife or rasp.

There have been too

many methods and measurements applied to the hoof to possibly

count. This may just sound like one more in a long list. I

assure you though, that nothing is more important to the

soundness and hoof function of the horse than natural sole

thickness. If you doubt this, try rasping a little sole off of

your own foot; just a little bit every four weeks will do the

trick. Study the wild hooves and get an image in your mind of

the shape of the soles and particularly, the height of the

collateral grooves from the ground. The wild hoof below has a

wire placed in the bottom of the collateral groove to help you

visualize this on the radiograph.

If you make sure

your horses' collateral grooves are a natural height off the

ground, you will be amazed by their soundness and by your own

ability to fix and prevent hoof problems. Nature was kind to the

horse to provide such an accurate guide for us to follow. As

usual, we just need to learn to listen.

Added in 2018:

Since the collateral grooves tend to be 7/16” (9mm) away from

the corium, if you concave the sole all the way to the bottom of

the collateral groove around the apex of the frog, you will have

cut the sole too thin (right side of drawing). In order for the

entire sole to be of adequate (5/8”-15mm) thickness (much needed

for safety and soundness), there needs to be a 1/4-3/8” (6-9mm) verticle

dropoff into the collateral grooves adjacent to the frog

(left side of drawing). Note that the collateral groove

heights-off-the-ground are the same on both sides, but the left

side has a much thicker sole.

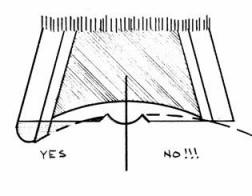

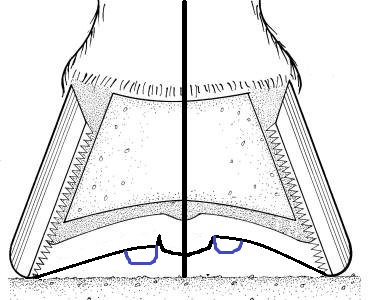

The same

reasoning is important when considering the sole ridges that

tend to pop up along the sides of the frog. On the right side of

the photo (with the excessively thin sole), the sole ridge

(blue) is simply the horse growing adequate

sole thickness in that spot – leave it alone, and hope that

adequate thickness spreads to the rest of the sole. Look for

that 1/4” dropoff into the collateral groove. On the left

side of the photo, there is a 1/2” dropoff into the

collateral groove – this ridge of sole has formed on top of an

adequately thick sole. It might be appropriate to trim this

ridge off so that the dropoff is only 1/4” deep, though do

consider that it might also be a terrain adaption (See the

article

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Seasons.html).