The Bars

(10-25-06)

with 2018 edits

Pete Ramey

Copyright 2006

"Please don't

twist this article into the thought that excess bar pressure

can't do harm. The bars, sole frog and walls each have weight

bearing responsibilities and excess pressure to each of them can

certainly cause problems. The change in my understanding,

thought process and trimming is that the bars “like” to share

more of the load than I previously thought. How much? It varies

from case to case; mostly by terrain, health and use of the

individual hoof." Pete

"This article works hand-in-hand with the previous

article,

One Foot for All Seasons?

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Seasons.html.

The ground surface of the frog and the outer

periphery of sole adjacent to the white line should rarely be trimmed on a

barefoot horse, but the area in-between the two is a very critical and

complex issue that varies with terrain, type of work and the health of the

hoof."

It is

impossible to "hit blood" during a trim if you understand the shape/function

of the internal structures and the critical need for uniform, callused sole

thickness.

The coffin bone provides the foundation for the front half of the foot; the lateral cartilages form the foundation for the rear half. In this domestic cadaver, everything that is not directly underneath the coffin bone and lateral cartilages has been removed. This divides the heel buttress down the center. In my opinion, everything left here (distal to the corium) is designed primarily for vertical support and energy dissipation. Everything I removed is primarily designed for protection from the elements (This includes the outer half of the heel buttress). The outer wall is a critically important shell, but a shell it is.

I see

and treat the heel buttress and bar triangle as a “fork in the road” between

supporting wall (the bars) and armor plating wall (the outer hoof wall). I

think of all the hoof wall material that grows from the bottom of the

lateral cartilages as "heel buttress." This includes the bars. It is

critical that you never look at a foot that was forged on varied terrain and

think of it in terms of mechanical forces while standing square on concrete.

The slope of the bars allows expansion, but this expansion should be allowed

to "bottom out" for support. Treating the bars as an important vertical

support structure will improve your progress with founder cases, or any

horse with a less-than-perfect wall connection and/or thin soles.

Few

professionals argue against the principle that vertical flexion of the

lateral cartilage is the primary shock absorber of the equine foot. Also,

everyone seems to agree that the heel buttresses should carry the load in

the back of the foot. The inner half of the heel buttress grows directly

from the lateral cartilage foundation and so does the bar. The transition

between the two is seamless. Why would support by the heel buttress be

correct, and support by the bars be wrong? They are the same thing. In my

opinion the mistake is to take the other fork and think the outer half of

the heel buttress and the outer hoof wall are primary in a vertical support

role.

Like most

natural hoof care

practitioners who learned at the same time I did, I came

from a traditional shoeing background, then studied the early

barefoot works of Jackson and Strasser and took their early

insights to the horse, searching for more answers. For years I

routinely trimmed the bars and the sole ridge that extends from

them (along the frog) to the level and flow of the rest of the

natural, callused sole plane without giving it much thought. I

saw a great deal of success, but in hindsight only a shadow of

what I see now. I was stuck in the thought that pressure to the

bar region needed to be reduced and kept to a minimum, even as I

constantly said, “Nature would not and did not put anything

on the bottom of the horse that was not intended to bear weight”

and “Nothing is passive on the bottom of the foot in varied

terrain; everything that casts a shadow bears weight.”

I believe the bar pressure phobia came

first from horseshoers, who see constant demonstrations that bar

pressure on a shoe causes local bruising and abscesses. This

gave many farriers the idea that the bars weren’t supposed to

bear any weight. But as with the sole corium, the bar corium is

damaged by

constant pressure, as with having a shoe

“clamped on” tightly. The bar corium, like the sole corium

thrives under

pressure and release only. There is a huge

difference between the two.

Then the early barefoot trimmers started

carving out the sole and bars from the back of the foot in an

attempt to increase the flexibility of the foot. The now

over-exposed coriums bruised and abscessed, I believe simply

because of a lack of armor. They mistakenly blamed excess bar

pressure, and carved them away even more. But I have found that

if bars are maintained at about a 3/4" thickness and the horse

is managed barefoot and booted, the bars are actually a strong

place to bear the brunt of impact force – nature put them there

for a reason.

In addition to that, there are countless teachings out there that try to convince folks that you can relieve corium pressure to an area on the bottom of the horse by thinning or concaving away its armor – just carve 1/16” of “relief” and POOF, no more pressure to the region, right? Perhaps if horses only stood perfectly still on hard, flat surfaces this might be partially true. But the second a horse steps into motion; the second it steps onto terrain the foot can sink into, the pressure to the corium is increased by carving away its armor. Never forget it.

This horse lives on a soft pasture and comfortably works on rocky terrain. Although the walls have been routinely managed, the bars have not been trimmed on this very sound front foot for at least two years. For that matter, neither has the sole or frog. The bottom of the foot has been allowed to find equilibrium in its growth rate. Remember that when a horse puts out 'excess' growth it is trying to recover from something..... Be sure it is not your trim!

Shod horses come out of shoes much more

comfortably if you leave 1/4” of bar wall standing above the

sole plane. This also immediately and very dramatically

increases the soundness and traction of most barefoot horses.

The bars will almost always start to maintain their own height

at the level of the sole or perhaps 1/8” to 1/4”

longer than the sole if you leave them alone. The less you trim

the bars, the shorter they become! The flip-side is that the

more routinely you trim the bars, the quicker they pop back and

“need” to be trimmed again. Leaving a longer bar (and sole ridge

around the frog) accelerates the process of achieving a deeply

concaved sole by providing support to the internal

structures and reducing sole wear. I already learned this lesson

about the other parts of the foot years ago. The less I trimmed

the sole, the deeper the solar concavity became. The less I

shortened the foot, the shorter the foot became. The less I

trimmed frogs, the sounder the horses were, and the frogs didn’t

get taller, just more callused. Every time I have learned to

back off, my horses became more comfortable and the

rehabilitation of pathologies accomplished more quickly.

I was a just a bit slower in seeing the same truth about

the bars. Now I’ve come to view them as a critically important

weight-bearing structure and see that as with every other part

of the foot, over-trimming them makes them grow too long, too

fast.

A basic guideline I'm starting to

embrace is this: If more than 1/4-inch of any part of the foot

“needs” to be removed at a four week maintenance trim, that spot

was probably over-trimmed at the last visit. Not by any expert's

standard, but by the horse's standard in its given terrain and

given the current health of the internal structures (the horse

will work overtime to replace needed material if it is removed).

This is a strong statement, I know, but I'm learning to trust it

more every day. How do you apply this? Not by just leaving all

of the excess, but by always leaving anything that

pops back

an 1/8-inch longer than you did at the last trim. You'll be

amazed as you watch the excess growth immediately slow down –

the hooves will move towards self-maintenance.

This does not mean you should allow a

flared bar to lay on top of the sole. If a bar is flared out of

any reasonable support role, I do tend to trim it to or just

slightly longer than the level of the sole to try to

encourage/allow straighter growth for the future. But people who

take this a step further – cutting sole and bar together,

looking for straight bar tubules near the corium are making a

big mistake. The real secret to straight, strong bars is

heel-first impact, and that type of trimming puts horses on

their tiptoes, perpetuating the problem.

What is "the right" bar length? As

discussed at length in the previous article

One Foot for All

Seasons? it varies dramatically with terrain. The bars need

enough relief (solar concavity or slope from the heels) that

they can descend as the hoof expands, but more importantly,

they need to be in place to "bottom out" to provide vertical

support at peak impact loads – transferring energy into the

flexible lateral cartilages. On hard, flat terrain, a 1/4-inch

taper from the heel buttress to the end of the bar might be

perfect. On rocky terrain, much more taper or concavity may be

necessary. On soft arena footing the same goals and support

ratio may require a bar to be longer than the hoof walls.

Severely foundered horses; particularly "sinkers" often love to

have all or most of their weight carried by the bars, as do

Thoroughbred types with wholesale lamellar separation..... I

wish it were easier, but honestly listening to the hoof will

take you to the right place.

Now enter the latest research from Dr.

Bowker. He and his team at MSU have discovered that much of the

intertubular sole material is actually being produced from the

bar laminae and migrates outward, flowing around the sole

tubeules, toward the outer periphery. This is something we

should have noticed in the field. Have you ever seen a hole in

the sole that was made by someone trying to dig for an abscess

or drain a puncture wound? Did it fill back in with new sole

material? No, it eventually migrated forward and out the front,

didn’t it?!

The results of the studies are not complete; the

research is currently ongoing, but it appears that

relatively little of the total mass of the sole is actually

being produced from the outer inch of the sole's corium – just

enough to help move the greater mass of sole coming from the bar

laminae along in its journey to the outer periphery.

This works much like the keratin cells

produced from the laminae aid in moving the larger mass of hoof

wall growth down from the coronet, except in the case of the

sole, the tubeules run straight from the solar papillae to

ground on a 45-ish degree angle, generally paralleling the

dorsal aspect of P3. Meanwhile, intertubular sole horn is

flowing from the bar laminae (and the solar corium adjacent to

the frog) toward the outer periphery. These new cells flow

around the sole tubules like a slow-moving river flowing through

a cypress forest. Dr. Bowker and I studied this both by

backtracking spots of pigment in the sole to their origin of

growth on cadaver feet and later in live horses, by embedding

BBs in the sole and photographing spots of pigment in the sole

flowing past the BBs over time.

This brings up some very important things to understand when trying to help hooves recover from various pathologies. Since the same structures (bar laminae) are responsible for producing both bar material and much of the mass of the sole of the horse. If the horse is constantly working to replace bar material you are trimming away, it can probably reduce the ability to build sole that would eventually be positioned under the toe! This is why it is important to try to achieve self-maintaining bars by leaving them a bit too long and thus slowing down their rate of growth. I believe it 'frees up' the bar laminae to send a larger amount of sole out to the distal border of P3.

[Admittedly, this has been difficult to

study. If you do something to a foot and it responds well, you

really don't know exactly how the foot would have responded if

you had done something different. I can say for sure that it

seems far rarer for a foot to refuse to build sole at the toe

when little or no trimming is done to the bars and sole ridge

adjacent to the frog.]

Secondly, when you see a thin-soled horse

with heavy ridges of sole along the frogs and/or wrapping around

the apex of the frog, realize this material is not necessarily

building upward into even taller lumps. Much of the material is

traveling outward, on its way to the callus ridge under the

distal border of P3 where it is needed most. This is why thin

soled horses tend to build these ridges and horses with thick,

concaved soles tend not to. The thinned soled horse is working

overtime to try to spread sole material toward the white line

and these ridges of sole should not be trimmed all the way down,

but should be allowed to do their job of vertical support and

sole building. Can they inhibit hoof expansion? Not as much as

the decreased movement caused by pain from thin soles!

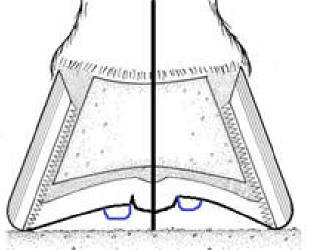

Since the

collateral grooves tend to be 7/16” (9mm) away from the corium,

if you concave the sole all the way to the bottom of the

collateral groove around the apex of the frog, you will have cut

the sole too thin (right side of drawing). In order for the

entire sole to be of adequate (5/8”-15mm) thickness (much needed

for safety and soundness), there needs to be a 1/4-3/8” vertical

drop-off

into the collateral grooves adjacent to the frog (left side of

drawing). Note that the collateral groove heights-off-the-ground

are the same on both sides, but the left side has a much thicker

sole.

The same

reasoning is important when considering the sole ridges that

tend to pop up along the sides of the frog. On the right side of

the photo, the sole ridge is simply the horse growing adequate

sole thickness in that spot – leave it alone, and hope that

adequate thickness spreads to the rest of the sole. Look for

that 1/4” vertical

drop-off into the

collateral groove. On the left side of the photo, there is a

1/2”-tall drop-off

into the collateral groove – this ridge of sole has formed on

top of an adequately thick sole. It might be appropriate to trim

this ridge off so that the drop-off is only 1/4” deep, though do

consider that it might also be a terrain adaption (See the

article

http://www.hoofrehab.com/Seasons.html)

The one part of the foot that can and does

replace lost material the quickest and most directly is the area

of bar and sole alongside the frog. The growth capacity of this

region is incredible and it doesn't have far to go. The bars and

the sole ridge that often extends from them (parallel to the

frog) can seem

uncontrollable in its rapid growth,

particularly when the laminae are destroyed or compromised in

the wake of laminitis and when the soles under P3 are too thin.

One reason for this is that the blood supply comes in directly

via vessels that are dedicated to the region. This circulation

is not reduced during acute laminitis or excess pressure to the

outer periphery of the solar corium. In contrast, the outer

periphery of the solar corium is nourished by blood vessels that

come in through the coronary corium, then feed the dermal

laminae, then the circumflex artery, then finally wrap

underneath to nourish the solar corium.

Is this capacity for growth an accident? A

mistake by nature? Something we should do battle with? I think

not. The bars lie directly beneath the lateral cartilages. They

are positioned perfectly to transfer impact energy directly to

the all-important, flexible foundation of cartilage in the back

of the foot. It may not be natural for this region to be in a

primary support role, but it can temporarily step up to the task

when the sole and lamellar connections are failing.

The sole ridge along the frog (the thickest

part of the sole), also nourished by the same pathway as the

bars, is positioned perfectly for direct support of the coffin

bone in the front half of the foot. The sole's corium is thin in

this region, but much thicker in the outer periphery. This

allows for expansion of the front half of the foot as P3

compresses the thick cushion of blood in its outer periphery

(between the distal border of P3 and the sole). For years, I

have felt that the sole is the primary weight-bearing surface of

the foot, but the more time I spend with Dr. Bowker, the more

strongly I feel the primary natural weight bearing (actually

impact bearing) structure for the equine foot is actually the

bars. In the healthiest of feet, the frog should start to impact

the terrain first, absorbing some energy as it compresses. Then,

the heel buttresses, thus the bars should start to hit the

ground, transferring more of the impact energy directly into the

flexible lateral cartilages. Finally, by the time the sole is

starting to transfer impact energy into the coffin bone, much of

the impact energy has already been absorbed. More energy is then

dissipated as the coffin bone loads and compresses the cushion

of blood underneath (Bowker '99). By the time the toe walls are

finally engaged, most of the impact energy has already been

dissipated. Indeed when a healthy hoof hits the ground

heel-first, there is comparably little energy or vibration left

to be absorbed by the rest of the limb and body.

It has been at least ten years since I

believed the outer walls were the primary weight-bearing

structure. It just doesn't make structural sense for nature to

so precariously hang the weight-bearing structure on the side of

the coffin bone and lateral cartilages. It seems equally insane

to think we should waste so much energy dissipating potential

built into the horse by doing anything that could cause the

slightest sensitivity in the back of the foot. When a horse is

sensitive in the back of the foot – voluntarily landing toe

first, ALL of the energy dissipating features of the foot are

completely erased. In all other hooved animals it is well

understood that the 'pads' underneath are to support weight and

impact energy – the hoof walls are armor plating to protect the

internal structures from blow from the side (kicking a rock) and

perhaps as a traction or digging tool. Why is it so different

for a horse? Only incorrect traditional thought, in my opinion.

That said, why were so many of us taught to relieve pressure on

the bars? And why have we ignored nature's attempts to rapidly

replace the bars when we trim them down to the sole plane? They

are the one structure most capable of direct energy transfer

into the lateral cartilages. The lateral cartilages are forming

the flexible foundation for the back of the foot so they can

absorb most of the initial impact energy so the bones, joints,

tendons and ligaments are not over-stressed.

In my personal journey, the more I've been willing to load the bars, the quicker I am able to achieve rock-crushing soundness for my clients. That's the less significant news, though. The same attitude about the bars accelerates founder and navicular rehabilitation. A radical idea? Perhaps, but give it a try – it works and you'll see the results almost immediately. Food for thought, “There’s no such thing as a good habit!” Think before you cut, and if you trim something away that pops back in two weeks, always know that you made a mistake.

The left

picture – front left foot, post trim the day I pulled the shoes. The lateral

bar and heel (left side of

photos) was rasped into balance with the medial heel (based on collateral

groove depth and callused sole plane, not the distorted hairline). The

medial bar was already slightly below the wall and was left alone. I was

leaving the heels/bars as long as possible to 'pad' the very sensitive

situation in the back of the foot. The horse came out of shoes very

comfortably, landing heel-first and four weeks later the heels have

opened up or

widened considerably. Although they were never trimmed, the bars are no

longer spread across the sole or laid over.

Why?

Comfortable heel-first movement. In the past I would have automatically

trimmed the bars to the sole plane because they were

laying on the sole.

In hindsight, this would have reduced comfort in the back of the foot,

forced a toe-first impact, and probably slowed down these results and caused

a need for hoof boots. Also, if I had trimmed the bars to the sole I would

have had an even larger amount of bar material to remove again at the four

week trim.

Is it

'prettier' to trim the entire foot down to slick, shiny new material? Yes it

is, until you watch the horse move.

Does this mean we should just leave the bars alone? Unfortunately it's not that easy. Like any other part of the foot, excess bar length can cause many problems, so we're still left with our usual tightrope walk – always teetering on a very fine line between too aggressive and too conservative. The P3 "penetration" below demonstrates a need for aggressive bar trimming.

Pre and post set-up trim:

P3 is lower than any part of the hoof wall and covered with only

Pre- and post-

second trim. Only when I returned did I find out I'd made the right decision

about the bars. In 5-1/2 weeks, they didn't

pop back,

but callused off at the level of the sole – this horse had immediately and

continually started using the back of the foot. The hoof wall has grown well

beyond P3 and the sole has almost achieved adequate thickness. The horse is

very comfortable on his pasture and paddock, but would need boots/pads for

riding or rocky terrain. If the 'excess' bar material had grown back, I

would have kicked myself for making a mistake and trimmed them less at the

next trim.

At this trim I

didn't change the heel height, and left the entire bottom of the foot alone

(other than wire brushing), only beveling the hoof walls to continue the

growth of a well-attached hoof capsule. At this point I am mostly waiting

for development of the back of the foot and frog callusing.

From the files of

Thomas Teskey, DVM: "These views are of the right fore of an eight year old

quarter horse mare during the rainy 2005 Spring season--she has been

untrimmed for the past five years. She lives on extremely rocky terrain when

not being kept in for riding/cattle work. Her sole depth and bar length are

exactly correct and provide her the protection she needs on the terrain that

shaped her hooves. Frog position comes closer to heel height during wet

periods when terrain is softer." TT

From the files

of Thomas Teskey, DVM: "These views are of the right fore of a five year old

Morab mare taken during the dry Summer season--she has never been trimmed,

period. Raised on the same rocky terrain, she performs flawlessly under

saddle, with seemingly unnoticeable wear to her hooves after days of riding.

Note her massive bar-heel structure providing for extra strength, secure

landing and purchase, a frog slightly recessed for its own protection, yet

positioned perfectly for support, sensitivity and traction. Her sole is at

least half an inch thick, with a good amount of dry material ready to

exfoliate as she travels.” TT

How are the bars supposed to be shaped? Let's look back to nature (to the most incredibly sound hooves in the world) with a fresh perspective and truly ask, rather than making demands based on our previous, manmade ideals. As usual, nature tells us, "It depends".

|

|

| Feral front hoof: Montana- Courtesy Robert Bowker VMD, PhD | Austrailian Brumby (front hoof)- Jeremy Ford |

|

|

| Prior Mountain Fronts- Catherine Jones | Feral front: California- Pete Ramey |

|

|

| Feral front: Oregon- Courtesy Cheryl Henderson | Feral hind: California- Pete Ramey |

Were these horses on the brink of disaster because of their 'malformed' bars? I don't think so.